The New Deal, arguably one of the forgotten eras of U.S. history, grew out of earlier, also largely erased reform efforts. The Grange Movement’s roots are in the mid-19th century when, after the Civil War, Midwestern farmers organized to oppose the monopolistic railroads and grain elevator companies that charged exorbitant rates to move their crops to market. At its peak, the Grange Movement had over 850,000 members in several states.

By the late 1800s the Farmers’ Alliance, another populist movement, fought back the robber barons. It grew to three million members, spreading the gospel of farmers’ co-ops, conservation, and mutual aid through a network of some 40,000 lecturers and organizers. The movement eventually led to the Populist Party, which garnered well over a million votes in the national election in 1892. Its platform included nationalizing the telegraph, telephone, and railroads, a graduated income tax, and “postal savings banks,” a solution often cited for today’s struggling postal service.

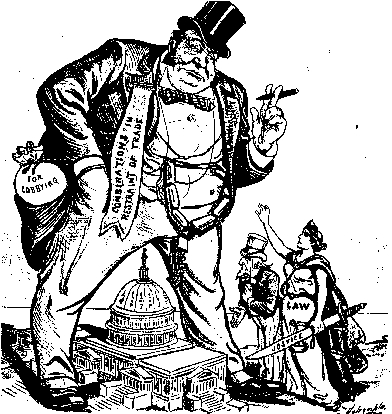

As the Farmers Alliance waned at the end of the century, muckrakers exposed Gilded Age injustice and corruption. Teddy Roosevelt won the presidency as a “trustbuster.” His successor, Woodrow Wilson, oversaw passage of the progressive income tax.

Following World War I, Wall Street went off the speculative deep end, bringing on the Great Depression. FDR’s New Deal revived many ideas of the early Progressives, including those of FDR’s cousin, Teddy.

Labor’s gains in the 1930s came out of FDR’s push for legislation requiring collective bargaining. The National Labor Relations Act in 1935 gave workers the right to organize, providing a counterbalance to corporate power. Empowered, unions pressed for the progressive reforms that raised the standard of living for the middle class and provided some economic security to the elderly, disabled, and poor. Both Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt were Grange members, and supported creation of a cooperative farm loan association to limit foreclosures. FDR’s “Second Bill of Rights” speech in 1944 posited that all humans have inherent economic rights.

The country’s turn to the Right in the 1980s and neoliberal austerity ever since gave tax cuts to corporations and the wealthy at the expense of the needy. Free market economics unleashed deregulation and moved to privatize the public sector. Union membership has fallen precipitously—thanks in part to so-called “right-to-work-laws.”

There are signs of resistance. The American Postal Workers Union has formed Grand Alliance Save our Public Postal Service. The National Trust for Historic Preservation, local activists, and city governments have sued the U.S. Postal Service over the sale of historic post offices to private developers. And millions of young people saddled with student debt are beginning to demand relief.

As history has shown, these are how reform movements start, and how Americans can come together again to address the biggest wealth gap since the Gilded Age.