This conversation took place on March 21, 2015 at John’s home in Mill Valley, California.

John Roosevelt Boettiger

John is the grandson of Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt

John, who was the person that most influenced you?

There isn’t any doubt that it was my grandmother, my mother’s mother Eleanor Roosevelt. We grandchildren called her Grandmère. I think I learned my basic values from her—her attachment to her family, her devotion to human rights; her absorption with the United Nations; her affection for Israel.

What are your early memories of her?

I was very young, but I still remember Grandmère getting off an airplane in Seattle and coming to stay with us on Mercer Island. Later, while I was still a young child, my mother and I moved to the White House during WWII, but I hardly remember her from that time because she was gone so much—overseas, visiting bases in the Pacific, London or elsewhere.

My memories of her are more vivid from the years I was a student at Amherst College. My parents had gone to Iran for two or three years, so she said, as was her way, “Johnny, if you don’t have a home to go home to, you have mine. Come to New York City or to Hyde Park, wherever I am.” And I did.

What do you remember of those times?

On Grandmere’s lap

Anna Roosevelt, Eleanor Roosevelt, John Boettiger, Jr., and Curtis Roosevelt. Source

There are so many memories…like when John Kennedy won the presidency from Richard Nixon and we watched it on television at her apartment on East 83rd Street, and when JFK visited her at her home in Hyde Park.

I can tell you she was sometimes a perilous driver. Her son, Franklin, Jr. owned Fiat dealerships in the Southeast—one of his many enterprises—and gave her a little Fiat sports car. She would talk animatedly while driving. At the end of her driveway onto Route 9G, for example, she would stop, look both ways, and continue talking, sometimes for a minute or more. Then she would take off without looking again. But to my knowledge, she never ran into anyone.

What do you remember of your grandfather?

FDR and grandchildren

Franklin D. Roosevelt III, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and John Roosevelt Boettiger, Christmas 1939 at The White House.

Photo Credit: From the Archives: First Families Celebrate the Holidays at the White House

I was the only child living in the White House during the war years, and I would be invited into his bedroom in the morning when he was reading his newspapers. The papers would be scattered over his bed. Despite the fact that he was paralyzed from his hips down, his upper body was extraordinarily strong. He would pluck me up from the floor and we’d sit together on the bed reading the funny papers.

I remember swimming with him in the White House pool, and playing in the Oval Office—not during important conferences, but when he was working at his desk. His desk was full of wind-up toys that I play with on the floor. And I remember my sense of kinship with the White House guards. But it wasn’t all fun. I felt also a sense of puzzlement and loneliness with my dad gone and my mother inaccessible much of the time.

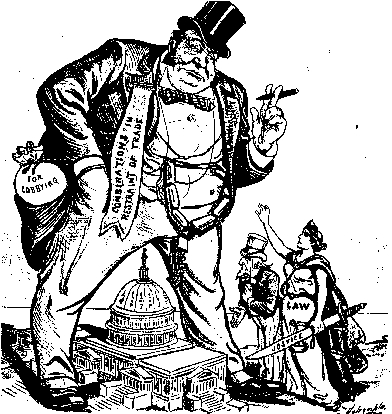

Talk a bit about your grandmother’s involvement in the United Nations.

President Truman appointed her as a member of the American delegation to the United Nations. She was naturally drawn to the realm of human rights. More than any other single person, I think, she was responsible for the creation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The only standing ovation that the General Assembly has ever offered anyone was for her when she presented the Declaration, and it was unanimously approved.

Could she have imagined the role the U.N. would play today?

My grandfather’s vision for the U.N.—and my grandmother’s nourishment of it—was that it would become principally an instrument for maintaining peace. The role the U.N., is playing today is diverse, and less vigorous than she would have wished, but I believe she would still be proud of it, and certainly working on its behalf if she were alive today.

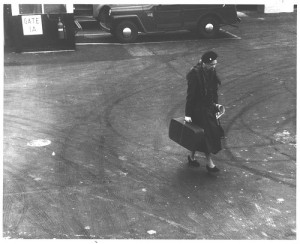

There’s a famous photograph of Mrs. Roosevelt walking toward a plane that’s parked on the tarmac, carrying her own suitcase.

There’s a famous photograph of Mrs. Roosevelt walking toward a plane that’s parked on the tarmac, carrying her own suitcase.

I never actually saw her walking with her suitcase. But she didn’t like entourages. Of course, she would have them periodically, but she was very independent and liked to travel quietly and without a big fuss. It was her style.

Do you recall your grandmother advising you that you had a special role to play, or advice on how to live your life?

I don’t think she ever spoke in that way. She felt that if I was going to learn, better to learn by example. She surrounded me with her own magic.

The complete transcript can be found here.

John Roosevelt Boettiger is a retired professor of psychology and a member of the Living New Deal Advisory Board.

Susan Ives is communications director for the Living New Deal and editor of the Living New Deal newsletter.